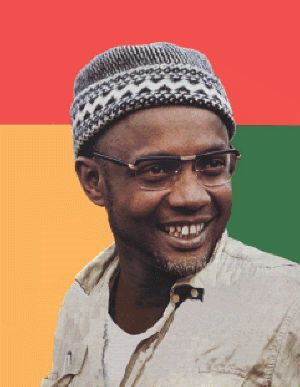

One of the major tools European colonisers used to develop and sustain their authority in Africa was the bifurcation of society into the ‘culturally superior’ elite and the ‘culturally inferior’ masses. Cabral identifies the roots behind this division, and highlights the significance of overcoming it for any liberation movement to be successful. In this piece, I will be commenting on the importance of the “reconversion of minds”, which Cabral also calls “re-africanisation”, for a liberation movement, and whether or not this reconversion was permanent or only existed for the purposes of independence.

Cabral points out that one of the major reasons colonizers were able to dominate such a large number of people for such a long time was the “creation of a social abyss between an indigenous elite and the popular masses”. Mainly in urban (but sometimes, also peasant) settings, this occurred when the petite bourgeoisie “assimilates the mentality of the coloniser, considering themselves culturally superior to the people they belong to”. The “colonized intellectuals”, as Cabral refers to them, then had no motive to drive out the coloniser since they felt no threat to what they now considered their own culture. In rural areas, the coloniser “assures the political and social privileges of the ruling class over the popular masses by means of the repressive machinery of colonial administration”. By doing so, they were able to heavily influence (perhaps even control) the elite group of society with “cultural authority” over the popular masses, therefore explaining why some European states were able to maintain control over their colonies despite never having no more than a few thousand of their own people there.

However large the apparent differences between the assimilated elite and the popular masses may have seemed, “non-converted individuals…armed with their learning, their scientific or technical knowledge, and without losing their class prejudices, could ascend to the highest ranks of the liberation movement”. It is important to note, however, their motives behind this involvement. Theses “non-converted people” considered this “the only viable means of succeeding in eliminating colonial oppression of their own class and re-establishing the same complete political and cultural domination over the people-and in the process exploiting to their own advantage, the sacrifices of the people”. Therefore, the intentions behind such individuals’ contribution towards the liberation movement were usually not pure. This becomes evident at the time independence is achieved, when the people who were previously victim to colonial dominance become victims to dominance at the hands of their African rulers.

For Cabral, any liberation movement should aim for “a convergence of the levels of culture of the various social categories which can be deployed for the struggle, and to transform them into a single national cultural force which acts as the basis and the foundation of the armed struggle”. In order to do this, the division between the elite and the popular masses, created (or widened) by colonial powers, needs to be shattered. To say that this single national cultural force still exists today would be inaccurate. Despite having gained ‘flag sovereignty’ decades before, many African nations continue to display signs of the cultural divisions brought about and enlarged by their colonists. Rwanda, for example, despite having officially gained independence in 1962, continued to display signs of huge cultural division between the Tutsis and the Hutus, which culminated in the Rwandan Genocide of 1994. More recently, scholars have highlighted how African elites and their contribution towards neo-colonialism have carried on the persecution of the popular masses. Therefore, if the dreams of Cabral, and many others like him, are to be achieved, there is still a need for the reconversion of minds, for re-africanisation, and for the convergence of different social cultures into a single united one.