Kimberle Crenshaw begins her talk on ‘the urgency of intersectionality’ by naming eight names of black bodies killed by police brutality in the last two years. The audience only remembers the stories of the first four, all which are stories of males. The stories of black females murdered at the hands of the same violence are not remembered. The Black Lives Movement has somehow left out the black women’s names from wider circulation, they simply do not garner the same kind of attention as the stories of their brothers.

Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to be able to name this ‘problem without a name’ that afflicted black women. This term allowed for the coloured woman who suffered from the double bind on grounds of being a woman and black to be able to be able to name her oppression. Bell Hooks discusses in depth how womanhood was synonymous with white womanhood and the Black or ‘Negro’ identity was synonymous with black men. Crenshaw uses the metaphor of the intersection between two roads to describe the position of the black female. If she meets an accident on the intersection between the roads of racism and sexism, what road did she have an accident on? Crenshaw argues that it is neither and both; the black female experience falls through the cracks of both movements that aim to liberate her and exists within an overlap.

Judith Butler in ‘Politics of the Performative’ argues that intersectionality in essence is flawed as it turns women’s rights into a a ‘woman’s issue’ rather than critiquing the power nexus that these problems exist within. This is further examined with the example of Rosa Parks’s story and how the agency is not with the person alone and how a movement can be complicit with the very forces it claims to oppose. Rosa Parks’s name is regarded as a prominent female face within the struggle against segregation. This is interesting as this narrative conveniently brushes to the side the women who refused to give up their seats before her.

Claudette Colvin was a fifteen-year-old high school girl in Montgomery, Alabama who refused to give her seat to a white woman nine months before Rosa Park. Colvin was returning home from school and was sitting in the coloured section. It was required that in the case of crowding in the white seated area that the coloured people leave their seats and move to the back of the bus and stand so no white person would have to stand. The bus driver looked at Colvin signalling that she get up and give her seat to the white woman and Colvin refused to do so. She began to scream ‘it is my constitutional right!’ and was forcibly removed from the bus by two police men. In an interview with ‘Great Big Story’ Colvin looks back on the experience and how she felt ‘Harriet Tubman hands were holdin’ me down one shoulder and Sojourner Truth hands holdin’ me down on the other shoulder.’ Colvin described how despite being terrified, she felt ‘it was time to take a stand for justice.’ Her case was one of the five plaintiffs originally included in the federal court case Browder v. Gayle, to challenge bus segregation in the city. This case was instrumental in ending bus segregation. However, her name and her story are not remembered as they did not at the time fit the criteria of the NAACP. Colvin was charged for violating seating policy and assault. She was also pregnant out of wedlock by a married man and too young to be the face of a movement. Her story was actively erased and Rosa Park’s name circulated. Parks was a light-skinned, middle-aged, working black woman and the media would interpret her name as that of a resistor, not that of a criminal.

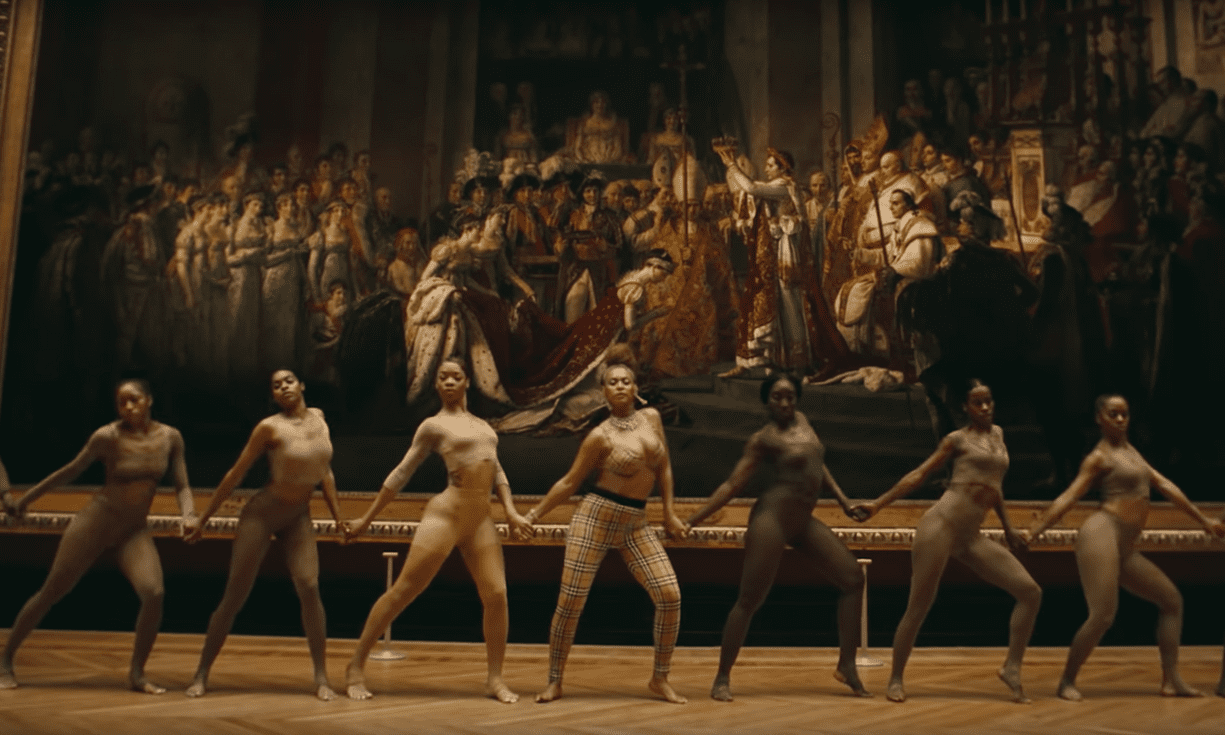

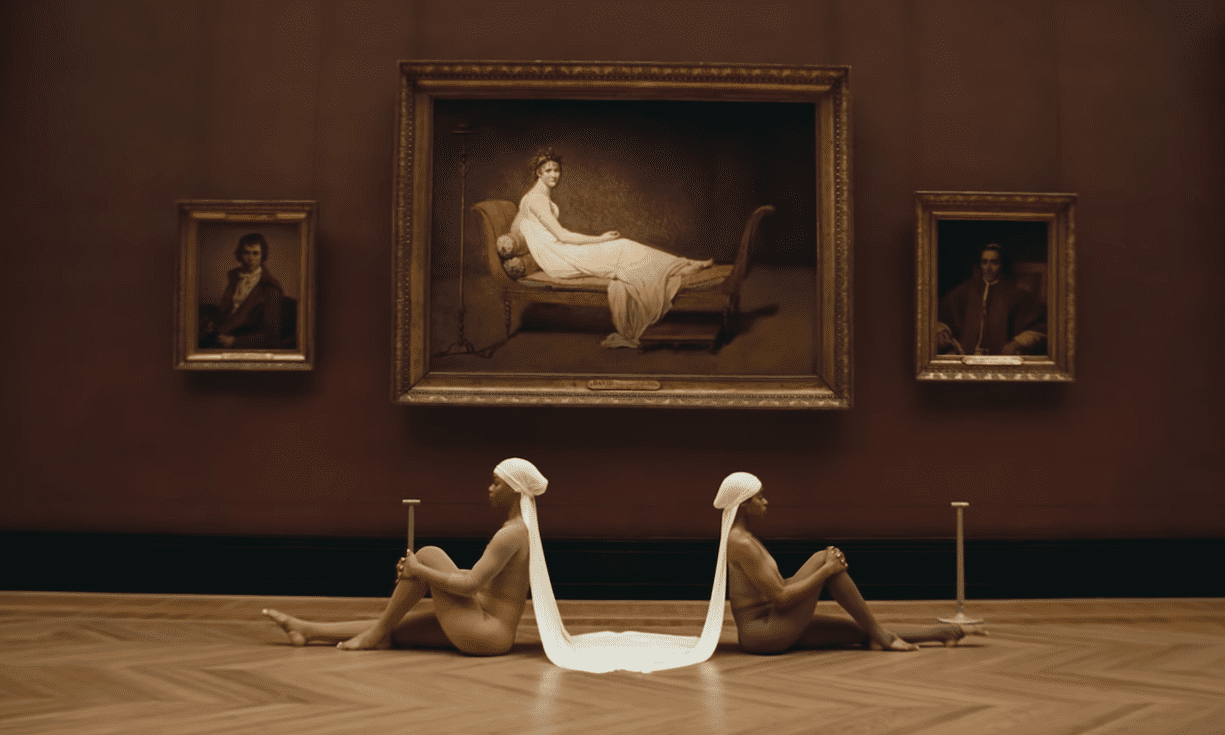

Kimberlee Crenshaw ended her talk by having the audience shout out the names of these black women and bear witness to their stories. Intersectionality is important because you can not address a systematic oppression without spelling out what that oppression is. Judith Butler and her critique reminds us to remember that the overlaps are not as simple as that between sexism and racism in black womanhood. The overlaps are that of class, purity politics, agism and how dark your black skin is. Butler reminds us to not try to gloss over these intricacies and to be careful of the power structures circulated stories operate within. The Black Lives Matter movement is an important, necessary movement given the rampant police brutality and violence. It is necessary to bring an intersectional approach to it and to question what the term ‘Black Lives’ means and if it includes the Black Woman aswell. The ‘Say Her Name’ movement aims to shed a light on this by forcing people to realise that police brutality against women exists in equal proportion. It forces you to think about the erasure of the Black Women and what kinds of Black Women are represented when they are allowed to be represented.