The Black Radical Tradition (BRT) has been a deep and winding journey into the ideas and events which created the Black struggle for emancipation. But, while the has been deeply moving, it did make me long for my radical tradition. About my Selma March, my Black Panthers, my Black Pride. But BRT can exist for me, and can also provide a blue print on how to have indigenous discourse on resistance. The Black Radical Tradition has much to teach South Asians about the importance of both the discursive and manifest ways resistance and struggle. I argue that through discursive introspection and proper documentation of struggles, we can at least begin to understand what decoloniality (or post-coloniality) means for us as South Asians.

Before this course, I felt like the Black Radical Tradition (BRT) was the furthest from my experience as a South Asian woman. We have not gone through the mass devastation and trauma that slavery (except perhaps those whose ancestors served as indentured labor). And, even within South Asia – whether one looked at individual countries or the commonalities between South Asians – there is deep internalized racism for anyone who was considered “black” (the state of non-being) whether they were religious minorities, ethnic minorities or anyone who does not fit within the norm. Perhaps it can be said that the BRT makes us question our histories, and what we consider as the norm amongst ourselves. In our insular communities, we fear the same abjection we force onto the non-being actors, and in this way systems of domination continue with new faces. And therein lies a unique trauma, one which we in South Asia (or at least Pakistan) have not properly been able to articulate. How does one begin to address this shortcoming?

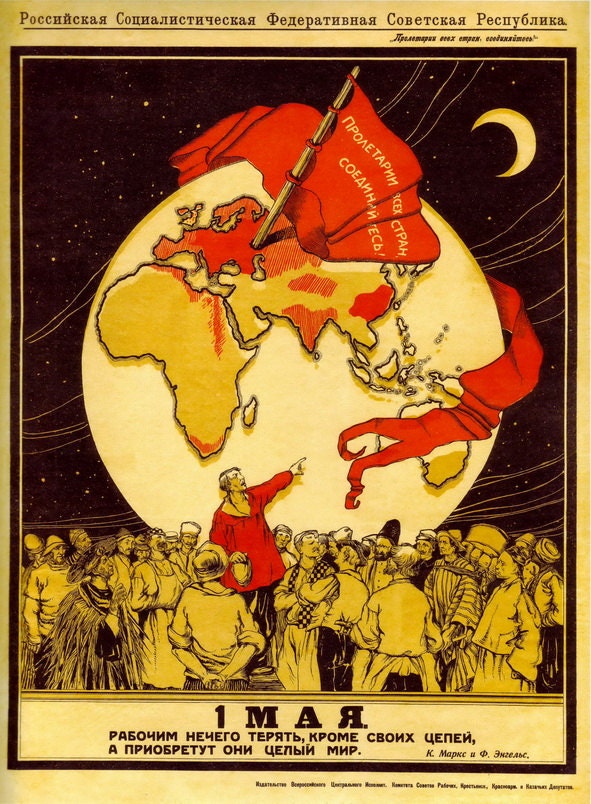

Firstly, we as South Asians need to stop considering BRT as something completely alien to our context. The point of calling it a tradition was to let these ideas pass from one generation to another as a coming-of-age, even if that meant the generation was in a completely different historical/cultural context. What BRT offers us is the ability to think radically. It has been the radicals who dared to dream of a completely new world free from oppressive and homogenizing forces. Not all of these ideas would be practical, but they move and inspire us to question the robustness and seeming innocence of the status quo. In the early 20th Century, WEB Dubois and Cesaire struggled for black people (or the colonized) to be recognized for their complexity and wholesomeness just as the white man was seen as complex and wholesome. But when these ideas became mainstream, the likes of Fanon and Malcolm X suggested new radical thoughts which sought the complete breakdown of race itself. A movement closer to my heart has the black women’s fight for intersectionality. At the time, it was seen as a deeply radical and even counterproductive movement, but it set a precedent for how women of color demanded more form the mainstream feminist movement.

But discourse also needs to be translated onto something concrete, and perhaps the best way to do so is through the archive. Just as there were stories of black oppression and resistance, there are no doubt stories of anti-colonial, revolutionary struggle within South Asia which are yet to be recorded. Toni Morrison urged us to find the missing blackness in our stories, both as a way to make the narrative more holistic and to allow representation to those who were otherwise left out from mainstream narratives. The people who have existed within our marginalities (Pashtuns, Baloch, Christians, Ahmedi) should be allowed to articulate their experiences in their own terms, without our impositions. But one way for us as privileged members of society to show support is to record their words, and disseminate them to the pubic. Thus, the act of archiving and citation can become a vehicle for allowing marginal narratives to diversify our common histories (the word common here means these histories are shared but also are also uniform and uninspiring).

BRT can be mine because it teaches me about my oppression, but it also has the power inspire a more South Asian tradition of historiography and discourse. Anti-colonial and racial equality movements were once considered radical and dangerous, but now they generate feelings of pride and unity – a radical tradition. We as students of history need to extend that same sentiment to those who remain on the peripheries of our stories. Then, can we create our lacuna of narratives, experiences and memories that bring about a sense of pride in our South Asian Experience. The narratives of oppression and resistance in South Asia (whether anti-colonial or post-colonial) are mine, but I can only recognize them if I put in effort to pay attention to them, just as those of the BRT paid heed and tribute to the journey of their movement.

.jpg)