Southern trees bearing strange fruit/Blood on the leaves and blood at the roots/Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze/Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant south/Them big bulging eyes and the twisted mouth/Scent of magnolia, clean and fresh/Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck/For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck/For the sun to rot, for the leaves to drop/Here is a strange and bitter crop

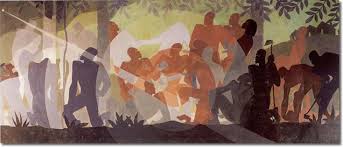

When Nina Simone sings, it is a lament for the South – a South that has allowed horror to root itself into the earth. One thousand, nine hundred and thirty reported lynchings is the total – slavery and violence, man’s cruelty to man, is now part of the South’s geography. The poem describes it so poignantly how nature, unable to comprehend such violence, is forced to accommodate such horror – to stand as a witness, to do all that it can do to what is left of the violence – the dead body. Nature is the only force that can look at so sick, so dead a thing hanging on a tree, and consider it some “strange fruit”. It’s a consequence of ignorance – lynching is not part of nature’s vocabulary. We, who have various words for various kinds of violence are not like her. Nature calls it by what she knows; a fruit – so strange, so bitter, something that doesn’t fit. It will attend to it, regardless of it’s difference – absorb it into the earth, let the elements merge them into one – the rain will gather it, the crows will eat from it. To us readers, listeners – who know, who are cursed to know the reality, the truth, we are ashamed by the haunting simplicity and perhaps, innocence of the description of the bodies, and the horror in the juxtaposition. We have defiled so beautiful a world – so much so that the scent of magnolias can exist alongside the smell of burning flesh.

I read up on who wrote the song to understand the poem better. Abel Metropole, a Russian Jewish immigrant to the Bronx, was a literature teacher who saw, one day in the news, a picture. A lynching in Marion, Alabama, that picture of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, both teenagers, hanging off the branches of a wide tree, their necks snapped, their eyes closed. That picture. They were dragged from jail and murdered by a wild, white mob, who, all together, are in the picture, too. Metropole, I sense through his poem, was struck by the sight of those boys who were hung, saw how the trees were made to carry the burden, the weight, of their bodies, and so, wrote this poem. And now, I understand why. He chose nature as his vantage point to look at the sight because nature is the only humane element in the picture itself.

The alternative are those who committed the violence. They are who I always focus on when I see the picture. What frightens me are those wild eyes, those smiling faces, who stand, relaxed, proud, below the hanging bodies, as though the sight is routine, as though they were captured strolling down the street. So lax, to casual, so matter of fact are they! What do they see? What do they think they’re doing? Men and women, together, they’re even wearing hats! One man points, resolute, at the figures above him, eyes dead into the camera, telling me, “This is who we are – this is we have done!” What is it you are trying to tell me, you – with your resolute finger? Why are you proud, you monster, you’re parading around death! To bear witness through poetry, I would not choose such figures as my vantage point.

Metropole is proof that men of heart, men who recognized the atrocity, existed at the time. His work is a profound act of empathy – that not only understands what kind of violence has been wrought, but seeks to tell it in a manner that adds beauty into the world – that depicts the lament, the moral outrage of the earth and those whose hearts are still in tune with it. Nina’s voice takes what Metropole created a step further – she turns it into a prayer, a mantra for healing, with her low, rich voice – a black woman’s voice, nature herself – deeply sorrowful, uncomprehending, but attending to her task. She sings to speak of the violence, but to also remind us that nature, that earth, is on the side of those who cannot comprehend the violence man creates, to heal those who are victims to it.