A central theme to decolonization is the reclamation of a humanity denied. This is what every thinker strives for – in outlining a humanity specific and special that is the sole prerogative of the colonized; in envisioning the world race-less and truly decolonized; in reclaiming the existence of a history – and not just a history but a great history.

On the last note, CLR James is not so different than, say, the envisioners of a great African past. He too makes a claim for the importance of a certain people based on primacy of history. In placing the center of the narrative squarely on Haiti as an agent, a definer of change and revolution in the world he inverts an accepted trope – that no revolution is not white somewhere, that all revolutionary ideas stem from Europe.

The trope is not unimportant – in some sense its the underlying theory of colonization: that the world is merely a stage for the European to act out his great destiny and all other people, cultures and history are but two dimensional props and faceless scenery -people that only become animated as the Europeans, the protagonists of their own histories, start to interact with them.

Thus CLR James takes the story and upturns it. The props are no longer window dressing, they’re the stage. The background actors are the stars. The previous protagonists – the ones that went through a crisis arc and gained a better understanding of humanity over the tragedy of millions – are mere villains – their character arc is no longer about redemption.

And in doing it he owns the stage.

The world is reformed. He claims the narrative as his – and claims in doing so, a history not of the fumbles and indulgences of the colonizers, but a history of revolution. For a moment the world is Haiti – and Haiti claims the right to be the entire world in that instance. It claims pride of place and all of history is rendered in relation to it.

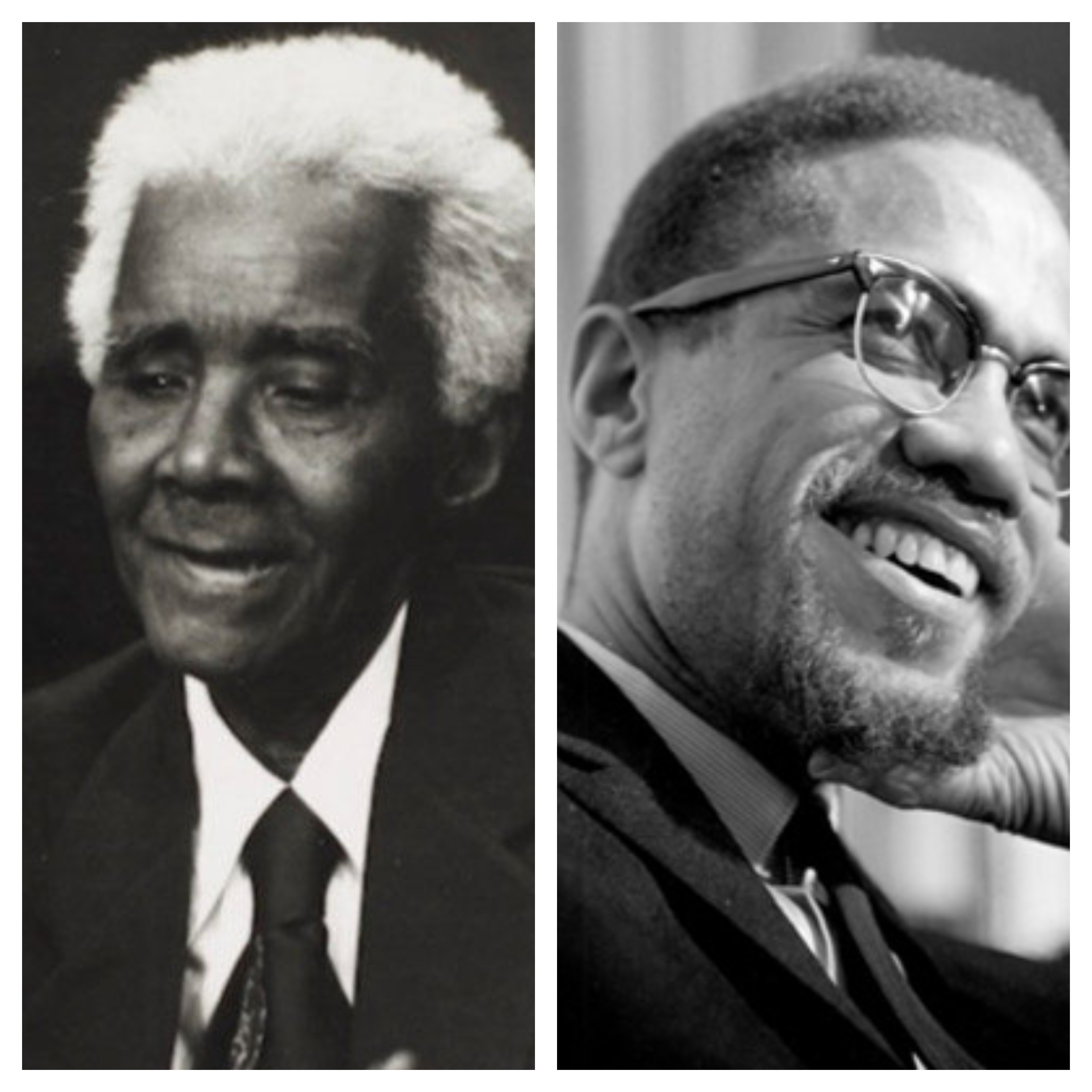

This capacity of – owning oneself, not as incidental but as human, as protagonists of their own story, perhaps, is the element that Malcolm X, in all his incarnations seems to never compromise on. Its the reason he’s talking, really – he isn’t really a preacher of Islam, however that may be defined.

Malcolm X talks of the ‘house negro’ and the ‘field negro’ – and the difference between them is the amount they adopt another’s narrative as more important than their own. The house slave is a prop in the story of his master and has thrown himself into that role wholeheartedly. His story becomes his master’s. The field slave has never had that privilege, if privilege it is. He owns his own existence out of pure stubbornness, impossibly harsh as it is. This story isn’t about celebrating the field slave, though. No, that would be in very different vein.

Malcolm’s story is about the house slave. It’s about the person who has lost his person-hood in favor of his subjugators’ – and it is about redeeming this person. He reclaims his own humanity. Preserve your life, he insists, because it is worth something. Fight back – be people in your own right. Don’t be second rate people in your own home, among your own people. His anger is emancipatory, his speeches revolutionary: ‘When our people are being bitten by dogs, they are within their rights to kill those dogs.’ There. He has inverted the narrative – his people are those marching determinedly towards a bright future, and are hounded by basic dogs.

This, then, is the hope – the need. To be people of the same level as all others. History doesn’t begin and end with the white man – humanity doesn’t begin and end with the white man.