The question of whether there is space for universalism in Senghor’s understanding is a complex one, that needs to be dissected while staying careful and conscious of the details he is hinting at. For Senghor, the idea of universalism appears to be incomplete without the affirmation and recognition of the “African” or “Black personality”, as he calls it. That warrants a few questions immediately. Is he inclined towards separating ‘blackness’ from the world or is he placing it within a larger universal framework?

While quoting the American Negro poet, Langston Hughes, he explicitly signals towards giving an independent expression to the ‘black’ personality, not bound by fear or shame. Again, this gives rise to questions. In terms of the universal, is the prefix to personality ‘human’, or is it specifically blackness? For Senghor, that is. His ideas unveil and delayer as we proceed. He views Negritude, “a sum of the cultural values of the black world” as a contribution to humanism. The recognition of it being a ‘contribution’ and not a whole, overarching theme suggests the existence of diversity and differences in the universal realm. Be it in ideas or languages, philosophies or religions, customs or literature, as he himself enlists.

Also, art.

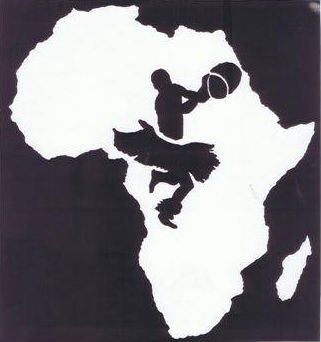

Senghor places a great emphasis on art and its location in humanism, and perhaps universalism too. Since he repeatedly addresses the various ways of conceiving life itself, it suggests that he is possibly not getting towards one form of existence, rather he is speaking in celebration and recognition of diversity. It is this recognition that gives Africa its place in the universal debate and discourse, otherwise, according to him, no one would speak of Africa.

Africa matters.

Africa must always be a part of discussion. One can break down his focus on the distinctness of the African identity into two strands. He might have believed that Negritude and the African identity would be lost in universalism. Secondly, it seems he was inclined towards the ‘particular’ more, just like Casaire. This particular-ness would not be possible without locating the ‘identity’ of his people in a universal framework, as opposed to letting it diffuse or even fuse perhaps. This is not to say that he views his identity or Negritude in isolation. On the contrary, he sees Negritude as a way of relating and engaging with the world, of contact and participation, where the black identity makes itself ‘known’. If here what is meant is a relative, instead of an independent existence, where then is the space of universalism?

In addition, a clear pattern is Senghor’s words is the discussion on ‘race’. It is important for Senghor and he does not ignore it to a greater, universal identity. He says, with reference to the world wars, that all the world powers were proud of their race. Therefore, his discussion on universalism does not quite look possible without situating the factor of race in it. Similarly, he clearly speaks of the contrasting offerings to the world, by Africa and Europe. While the traditional European philosophy tends to be static and objective, Africans understand the world to be a unique, “mobile reality”. This is not to say that the African is oblivious to the material aspects of being and things. They do recognize the tangible qualities of things which facilitate in understanding the reality of the human being. However, if a universalism is European (static, tangible) in its basic philosophy, then that leaves little room for Senghor’s, and Africans’, conception of a mobile reality comprised of various life forces. Interestingly though, at this point, Senghor does take into account how the Europeans and the Africans use the same expression for the ultimate reality of the universe. This is where he momentarily blurs the boundaries between the two, possibly creating space for a universal commonality.

However, soon after, Senghor moves on to the basics of morals and ethics, and here the African attitude again becomes separate. According to him, the African moral law is inseparably tied to nature itself, and every life force in the universe translates to a network of natural forces, which are ‘complementary’, or harmonious. Nature, consequently, brings with itself a certain human order. One that imagines man into a close knit society, based on various circles such as that of the family, village, nation or humanity itself. The African civilization values both the community and the individual. The notion of the particular again becomes apparent here. While group solidarity is important, the individual is not crushed or undermined. The closely knit society is the human society, made up of both contradictory and complementary life forces.

Negritude understands and also celebrates the ‘interplay of life forces’. Through these life forces, man journeys towards God and reinforces himself. This, for Senghor, is a journey from ‘existence’ to ‘being’.

Negritude lays the foundation for this journey, and enables itself to create space in the contemporary humanism, thus allowing Africa to make its ‘contribution’ to the “Civilization of the Universe”. In its contribution to the universal, it plays a part in international politics as well as in the fields of art and literature. For him, art is an expression of a certain conception of the world, of life, and of philosophy. Art is where Senghor, as well as the early explorers of African art, sought the human value, of a way of living, existing, being.

While it is difficult to ‘absolutely’ conclude whether there is space for universalism with reference to Senghor, yet one can deduce certain possible explanations. At some points, he refers to the universal forces, and the common expressions used for them, but does not hint at ‘universalism’ explicitly. He also discusses how the various forms of art integrate to create the universe, and perhaps his idea of universalism lies in this integration. He is possibly trying to show that universalism can come only via art, and within art stands out the ‘Black’ art, black humor, and black aesthetic. This again ties to the fact that perhaps Senghor does not want the African contribution, or the African art, to be lost or overshadowed in the cause of one universalism. In his negritude, universalism can not exist at the expense of what is ‘black’. He wants it to exist and stand out in the form of a harmonious, rhythmic song which expresses fundamentally the life of cosmic forces. These cosmic forces then trace back to the Being of the Universe; God.

Here it seems that his idea of universalism then, additionally, lies in the ‘origin’ of it, that is, going back to the one Source and Being of the universe. Or he probably believes in a universalism that is based on complementary cosmic forces forming a beautiful rhythm of harmony and union.

One thing, however, is clear. Universalism cannot exist without Africa’s contribution, and the space for a discourse on universalism can only come through the idea of Black African art primarily. Therefore, if a space of universalism does exist for Senghor, it will be of ‘blackness’ as one of the fundamental values. It has to come through keeping blackness as one of the ‘particulars’.

In other words, Universalism needs to be a function and expression of the black identity and black distinctness, to qualify for Senghor.