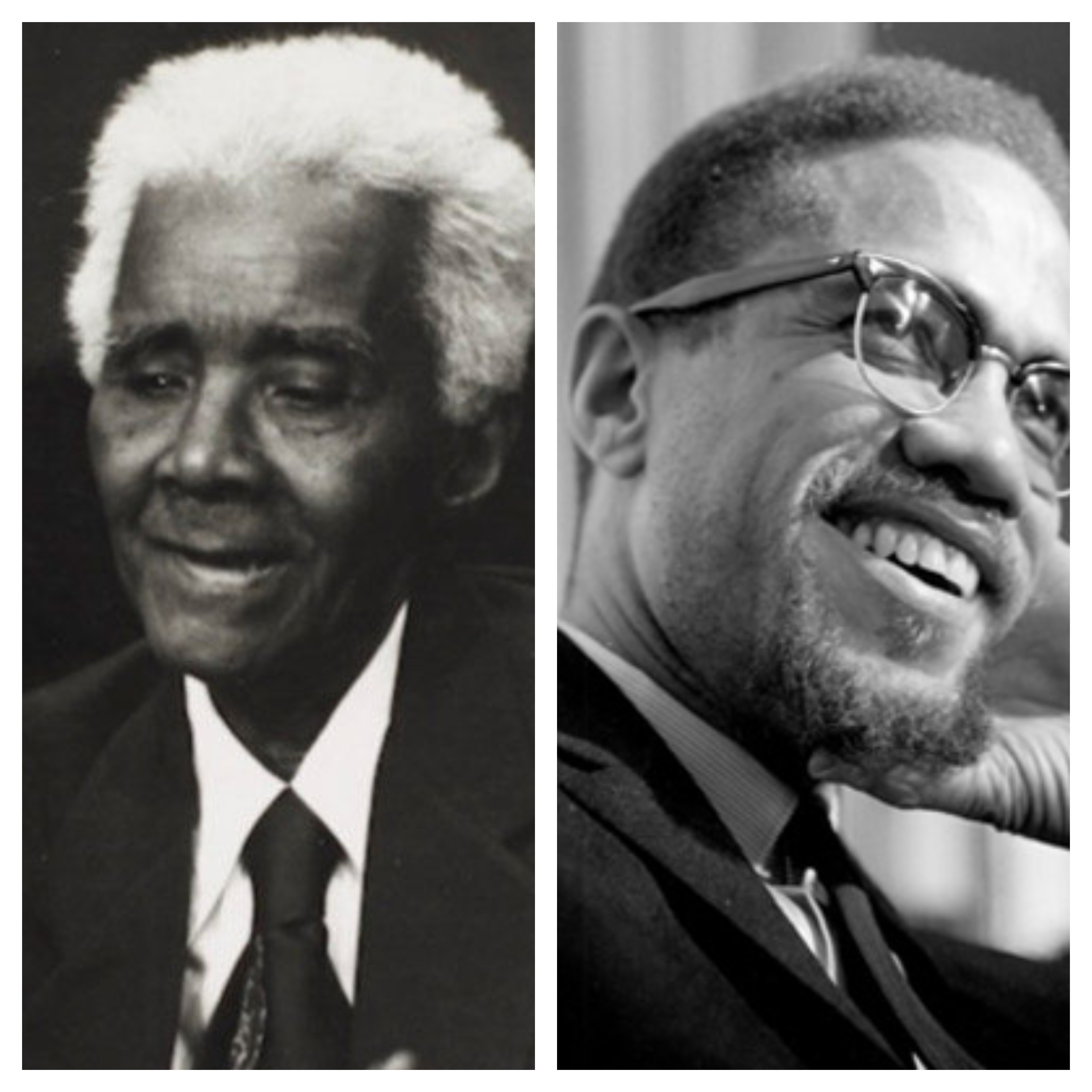

The question of whether Malcolm X and C.L.R. James can be viewed in the same light is an interestingly complex one. I would use ‘rays’ of light in the attempt to understand one through the other and try to find one’s reflection in the other, for ‘light’ in itself is what they both were, and are. I have only, so far, reached the rays.

In his work called “The Black Jacobins”, James begins with the chapter called ‘Property’. What an intelligent, provocative and tragic word in the sense that he uses it. Needless to say, a purpose and an intent can be derived from it. The word ‘property’ alone, immediately evokes a sense of emotion and anger, uneasiness and discomfort. A necessary discomfort and unease, i would say. And this is primarily what Malcolm X did when he spoke. He invited discomfort, strain and sweat, he invited the truth that some realized and others didn’t or perhaps were forced not to. In this sense, both James and X are holding out and urging everyone to see and to recognize the torches of truth.

In Malcolm’s speech titled as “The house Negro and the field Negro”, the ‘property’ in James’ “The Black Jacobins” is perhaps what Malcolm is referring to when he speaks of the ‘house’ Negro. The Negro, the human being, who was made to be considered a property of the slave master, a debt to the master, answerable to the master, and indebted to feel a sense of pride by denying themselves agency, own will and independence for the sake of being in close proximity of the master. In other words, when James recalls the physical torments faced by the ‘property’, Malcolm brings into attention the psychological impact and its manifestation in the minds of many Blacks who were made to live as property for hundreds of years. While James sees the slaves through the lens of what was imposed and forced upon them, Malcolm also takes into account how some slaves reacted to that imposition by submitting further to the masters and perhaps deriving some sense of pride from it. Here one might sense a complementary relationship between James and Malcolm, while, of course, appreciating the uniqueness of both in viewing and expressing the question of slavery and the then present condition of the black people.

When James speaks of the dark past, he is vivid. Painfully vivid. He narrates the journey that every slave would have embarked on when they were taken away from their land, their home. He tells how they lived, and how they died. How they protested, even in their deaths. Perhaps James is more inclined towards the journey undertaken by the slaves, and their sufferings that made them what Malcolm could classify as the field negro and the house negro. James is probably setting the stage for Malcolm to build his classification on, and to give his voice on. It feels like both are standing at different stages of the same history which has been cruel, unfair, unjust and agonizing for the Africans. They are both talking about the same thing, but the tones, the lens, the emphasis is unique to each. There is tragedy, and a very close association to the on-going tragedy, in the words of both. They choose to speak about it.

In terms of expression, both occasionally use sarcasm and wit to express what they strongly feel about. Maybe wit was their way of balancing their emotions, when repeating, recalling and re-identifying the sufferings that had penetrated into their present. This is especially true for Malcolm. No matter how much he and his audience laughed during some of his speeches, he knew and they knew what he was saying and what he meant even behind the veil of the laughs. Similarly, when James starts his work with two ironic sentences about the hypocrisy of Columbus, what is his ironic style doing. Why is there an impactful use of irony, strong language and wit. The answer is simple, and it lies in the beautiful fact that they were both artists. They knew art, they recognized art and they spoke art. It is their words embedded in art and the language of art which has given immortality to them, their imagination and their extraordinary audacity.

The story that James is narrating, Malcolm is directly addressing the sufferers of that story, urging them to bring their suffering to a halt. He is telling them directly to know their rights and to change their conditions. His work does not end at narrating and recounting the miseries and pains, the blood and deaths, the homelessness and injustice of the past, but his work and his voice are dedicated to bring an end to the past, on his and his people’s terms. The past does not stop or blur his imagination. Malcolm is thinking present. Malcolm is thinking future. He is taking James’ story ahead. Malcolm is thinking hope, however his hope is neither theoretical nor imaginary, and neither utopian nor effortless, his hope is one which requires effort, action, determination and the compulsion of proudly ‘knowing’ what is one’s right as a human being.

Both him and James are also interested and deeply invested in the question of location, of situating the black people, making them visible out of the racist boundaries confining their existence, their imaginations and their potential. To address the question of location, they use what they own in abundance. Memory.

When going through the words of both, one may occasionally recognize the distinction between a historian and an activist. However, i will not confine the two to the prefix of either being a historian or an activist. They were obviously, undoubtedly and evidently much greater than the two or three labels or professional titles attached to their names. They were artistic existences. And art does not belong to a definition or a title.

Other than the aforementioned (sometimes abstract) commonalities and complementary reflections of Malcolm in James and James in Malcolm, perhaps the most striking and bright point of convergence, which brings them into the same rays of light, is the ‘courage’. Their courage, their audacity and their choice to recall, to speak, to make known what darknesses and veils were holding within themselves. If James was telling history, Malcolm was seeking to overpower that history while keeping its memory alive, and taking direction from the memory.

It is this memory, this courage and this voice that bring C.L.R James and Malcolm X together under one light, illuminated from one source and spread in both overlapping and distinct rays.