The world has witnessed many an extraordinary moment. Moments that shifted not only the surface but also the substance of the world, or at least this is what the extraordinary, unbelievable moments promised, and dreamed. It is, therefore, an art to appreciate the strength and might of those moments and decades, following their emergence. I say decades because the time in reference here is not a distant history, neither has it lived through centuries. It will, but just not yet. The memory is fresh, and recognizing the very fact that it has not been long, is enough to make one pause every thought, enter into an epoche and solely devote the mind and the heart to understand, appreciate, and root for the revolutions of the twentieth century. The struggles, the convictions and the fears. What is crucial is to appreciate the powerful, terrific moments not in isolation, but in togetherness. Together in the fight directed against oppression, force, tyranny and conquest. A fight that lived through decades, sacrificed immensely and finally broke through the chains of time, a time undefined and inescapable. A time that was robbed, but that time also gave the motivation and strength to defeat the tyrannies.

Inconceivable yes, but it did happen.

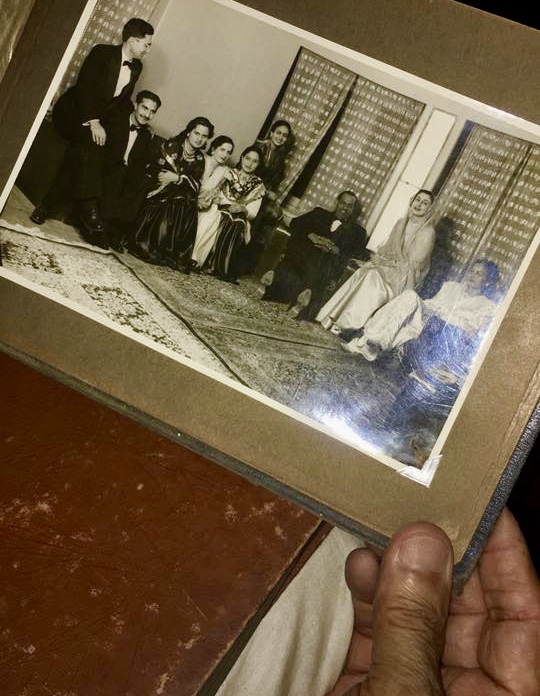

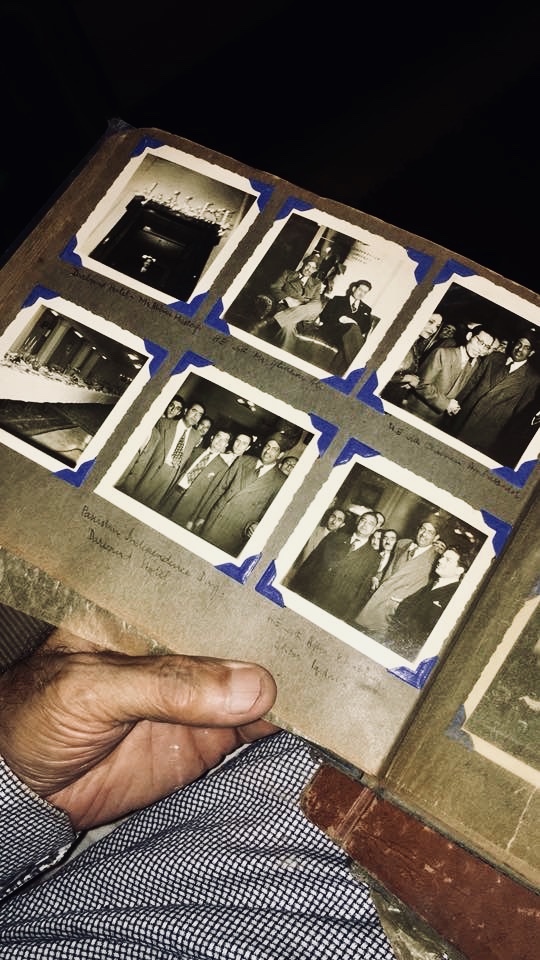

This fight was as much as Amir Haider Khan’s (Dada) as it was for Sukarno. As much a fight for those fighting for independence as it was for the communist revolutionaries marching to their capital from every corner of the world. Victory in sight, memory of the past and endless hope for the future. The contexts were different but celebrations the same.

Sukarno, in his speech, celebrates the coming together of the new Afro-Asian states in Bandung by ‘choice’, not by necessity. He recognizes their victory in gathering together, not dictated in a foreign land, but in their home country, having seen similar histories of violence, conquest, robbed representation and injustice. This idea and celebration of togetherness was reflected in Dada’s memoir as well. For him, it was a celebration of the coming together of communists from around the world to a ‘home’ that not only welcomed them but promised to provide for their future fights and transformations. A hub that united them under one flag, and one past, though lived separately but under the burden of one reality.

Sukarno was envisioning the unity and wave of fresh, free air that Dada was in fact ‘living’ and breathing in, during his time in the Soviet Union. This was the unity that Sukarno was dreaming for his nation and the nations that had emerged into light and life with his.

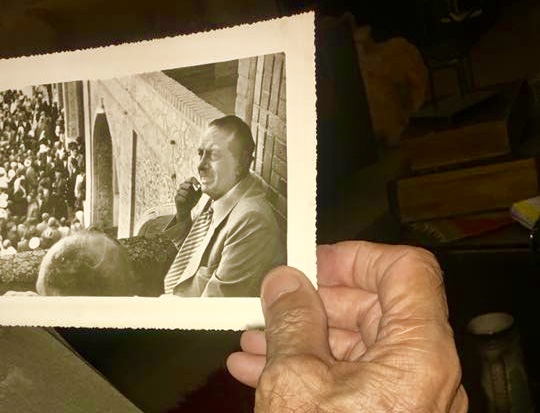

In Dada’s world, the racist, unjust, unequal forces had been defeated, or at least he was now out of their reach in the land that had promised him and his comrades the dignity, value and respect they had craved. Dada was in a space that accommodated one and all, bound by a common deeply-embedded ideology. Years later, Sukarno was stressing over the very need to unite, to recognize the urgency of a ‘sustainable’ togetherness. Reading Sukarno into Dada, one cannot help but realize that what Dada had experienced in terms of freedom and liberty was what Sukarno was desiring, idealizing and praying for. How Dada and his comrades’ lives changed in the Soviet Union was a reality. The words of Sukarno were a longing for that reality. For the likes of Sukarno, Dada’s memoir could be a model not too old to replicate or desire, but far more complex and difficult to achieve. Perhaps, that is why one senses a strange and uncomfortable fear in Sukarno’s speech. In his words, there was less to celebrate and more to fear, to recognize and to work on. There was urgency. There was a search for fraternity. The more one reads through it, the more manifest it becomes.

Sukarno refers to him and the attendees as “Masters of our own house”. While he celebrates the solidarity and agency, he also fears for it. Dada was in the new capital of the world, which stood in direct confrontation against the empires, capitalism. Sukarno knew that there was no one uniting hub for the new nations. They were on their own against the giants, and he recognized the new faces these giants had now taken, in the form of agonizing economic and intellectual control. That was, in the fears of Sukarno, another wave of colonialism. Much to the magic of time, the questions and dreams Sukarno had in his vision reflected exactly those that Dada had questioned and sought answers to for his homeland, India. Why couldn’t the same happen to India, he asked. There was struggle and sacrifice in India as it was in the Soviet Union and elsewhere, why then could the Indians not come out victorious, he would ask. In Sukarno’s universe, they did come out victorious. But could that India, or that Indonesia, promise the kind of power, liberty, equality and most of all, dignity, that the young Dada had lived in the Soviet Union. Was reaching freedom and liberty in its true sense simply not achievable, given the dependency of the new states on the predatory world. Dada saw a center which called him and his comrades from every race, color and country. It was probably that center which Sukarno had in his eyes, but only in the abstract. No defined structure of that center, neither a defined path to embark on. Instead, what Sukarno and his comrades had was an idea, or an ideal, not as easy to accomplish as words felt. Hence, the heaviness and fear in Sukarno’s words, which had immediately recognized that there were many colors of freedom. They had discovered just one.

What is apparent is different stages of a ‘single’ reality; the reality of being (treated) human. While Dada had lived that reality, Sukarno was promising to make it happen.

Thus, one reality was lived, one was dreamt.