Both C. L. R. James and Malcolm were revolutionaries of their time and in many ways similar in their goals. Before them, historical narrative was taken over by the white man. They began the practice of writing histories very different from what was the norm. They rewrote the singular, linear idea that the white man discovered the world and instead talked about how that world already existed and was inhabited by people of its own. The goal was to revise history, to mark different events as important and change where history begins from.

Both their writings analyse the intricacies of revolution and provide a very new take to them. C. L. R. James rejecting to view the Haitian revolution as a mere footnote of the French revolution was beyond revolutionary in his time. It challenges the widely accepted colonial notions. Rejecting the Western view and white supremacy was a remarkable feat. He wanted to allow the Africans to see themselves in a different light for once and to have the ability to create their own identity.

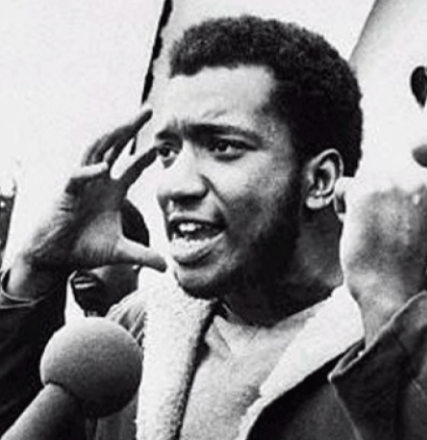

Whenever Malcolm X spoke his speeches also served as an alternative way to look at the world, a new take on history, much like James, through the experiences of the black people. He takes on a very assertive and reactionary approach pointing out political figures and criticising everything he believed to be wrong. He never held back. His speeches had a sense of urgency to invoke resistance within the African American community. He openly recognises the experiences of black people within America as separate from the widespread whitewashed narrative. He wants the Africans to form an identity of their own, separate from the American identity as their experiences diverge from those of the white Americans.

But both writers similarly talk about the creation of “Uncle Toms” who were complacent and never complained. These types of people were made the figureheads of the African community leading to a stagnation o their condition. Both of them wanted desperately to change this situation. They wanted to help the Africans realise their potential and to own up to their glorious pasts, the ones which were not written in the language of the West. They wanted to change who wrote history, how it was written and who deemed what events were of significance.