Contemporary day Western feminism might as well be used as a euphemism for the hegemonic feminist theory, for both are non-class, non-racialized, at least according to Mohanty.

In this world of polarised communities and strong power structures, Chandra Mohanty, in her essay, Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses, goes on to identify gender as a source of oppression. However, her take is quite different from ones common idea of gender struggle. She does not look at the man-versus-woman debate. Instead, she takes a more globalised view of the world and pays close scrutiny to how women of the West may well be waging a gender war against other women, or particularly those of the Global South. For me, Mohantys article was able to achieve three main things: the need for creating an understanding of how all global systems work in symbiosis (for instance, capitalism, globalisation, imperialism etc), the need to understand how the “Third World Woman” is in fact, constructed from the perspective of the “First World Woman, and the need to understand the detrimental effect of generalisations.

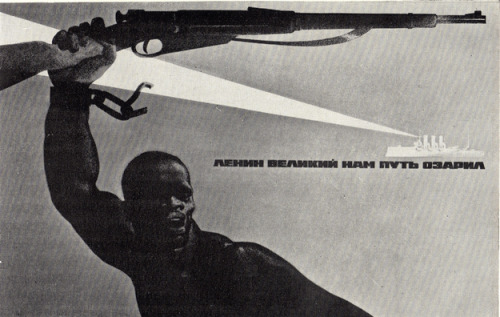

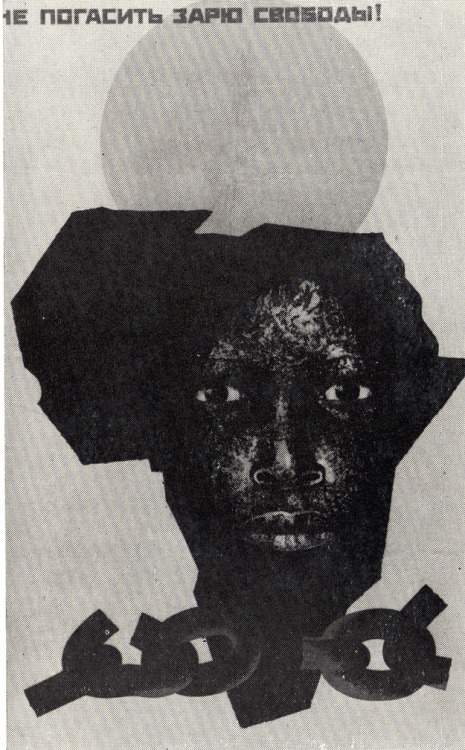

Keeping in view the colonial past of most countries (both, colonized and colonizer), and their present of globalisation and capitalism, it is almost impossible to look at any aspect of these given communities in a solitary manner. According to Mohanty, “western feminist scholarship cannot avoid the challenge of situating itself and examining its role in such a global economic and political framework. To do any less would be to ignore the complex interconnections between first and third world economies and the profound effect of this on the lives of women in these countries.” This analysis is particularly important for it brings to attention how ideas like imperialism, militarism, capitalism and globalisation are not to be looked independently, for all these systems practice in an interconnected manner and sustain each other. But it isn’t only their compounded nature that one has to call attention to. No. In fact, it is a lot more important to assess how at the heart of some of these practices are gendered and heteronormative sexual politics and ideologies that cement this kind of imperialism and militarism, further strengthening ideas of gendered oppression. Similarly there is a need to always answer questions of freedom and liberation (of the colonized) by deeply engaging with its imperial past and the epistemological question of decolonization and imperialism itself. This is pertinent in understanding ideas of decolonisation on psychic or social levels, or in terms of racialized gendered ideologies.

When Edward Said calls attention to the orient, he mainly lays focus on the need to look at it from the view of the occident and how the latter creates the former. This implies that when a French man goes to Algeria and looks at her people as “backward and primitive”, he is in fact, assuming himself to be at the pinnacle of progress and hence, creating the identity of the Algerian as being different from his own i.e primitive. This same principal can be applied to women of the first world, and how they construct this “third world woman” as being oppressed and primitive. When movements like “Free the Nipple” become flag bearers of what contemporary day feminism should look like, white women look down at the covered woman of the third world and assume her state of oppression in relation to the amount of clothes she uses to cover herself. This train of thought, although common, is inherently problematic, for it is entirely based on the assumption that the idea of a free, liberated woman can be conflated with the “western woman” and how anything that differs from this definition may well be constituting itself as oppressed and awaiting progress. And hence, it becomes almost compulsory, at least in feminist scholarship, to look at the third world woman through her right and culture, and independent of any western thoughts.

But is it as easy?

Most western feminists studying the “third world woman”, almost inevitably comply to the negative connotations that the phrase itself comes with. Part of it may be attributed to ethnocentrism while for the most part, the loaded term can be blamed. The whole term “third world woman” itself points to the problematic idea of generalisation, and how all these women from the Global South are an assumed cookie-cutter model of each other- oppressed and far from progressive. As a result, the first world woman constantly feels the “need” to protect this third world woman, and to “enlighten” her with what real progress should look like.

How this may be put to action is a stark reality in itself.

In 2002, when George Bush is trying to build his empire through waging a war in Afghanistan, Laura Bush comes forth and attributes this intervention to the “emancipation of Afghan women”. Her husband constantly refers to those women as “women of cover” and those who are “oppressed and marginalised”. One may ask how his definition of the woman in the burka (“women of cover”) suddenly, and so nonchalantly, translates to the oppressed, but then the precedent is enough as an answer. The 19-year long war, which sees no future of an end, has further sabotaged the country and made it into a more stimulated cauldron of oppression and tumult, at least for the women. The Afghan woman is possibly more scared to leave her house, and if she does covering is a prerequisite, not because the “Taliban are oppressive” and demand it, but because there is no other way. Even if one hypothetically believes that the war has “liberated Afghanistan”, one can bring Laura Bush’s definition of the “emancipation of these women” and they still still look a lot more destitute.

Feminism is a powerful phenomenon, and while its allies grow each day, people who feel threatened by it also grow at the same speed- almost linearly. Some may deem those non-allies as women-hating, atrocious humans, but then Chandra Mohanty clearly leaves a room for why the woman in burka may “not need” feminism and what her idea of it may be.