“It is only in revolutionary struggle against the capitalists of every country and only in union with the working women and men of the whole world that will achieve a new and brighter future.” (Alexandra Kollontai)

Leftist revolutionaries like Alexandra Kollontai at the start of the 20th century did state that their idealistic goal of a communist and socialist future can just be achieved if there is a new understanding of unity of the working class on a global level. Communism has to be understood as a global phenomena and is not just tied to the Soviet Union. These ideas did challenge dominant hierarchies along racial and gender lines within the exploitative system of imperialism and the capitalist economic structure that it is based on. Communist internationalism has therefore be understood as a promise for the working class all over the world to break free from the ties of the oppressive capitalist to be able to be represented in an autonomous way of self-determination.

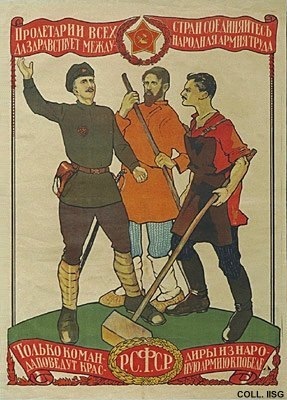

Being part of the proletariat is seen as the only important division of society that is used in order to shape a collective identity of the workers and farmers beside their cultural, racial or geographical background or gender.

One can argue that there is an inversion of social hierarchies in the way of how the class background is portrayed as the greatest value of an individual although always in connection to the collective working class as a whole. Dada Amir Haider Khan is describing in his autobiography Chains to Lose how he as an individual, orginally from the subcontinent who has worked on ships all around the world, is experiencing for the first time a sense of recognition and dignity while studying at the University of the Peoples of the East in Moscow. A place of unique diversity of people from various backgrounds mainly from the eastern part of the Soviet Union or the colonial and semicolonial East. A place where male and female students from all over the world of all ages and all different kind of educational backgrounds are studying and learning how “to assist in their national liberation movements against the imperialist powers and to organize communist parties in their countries”. Especially while recalling his experiences in the interview before getting accepted into the university it can be noticed that every personal detail like his social origin or his lack of formal education that led in the past to him being looked down on are now the qualities that are not just appreciated but even glorified.

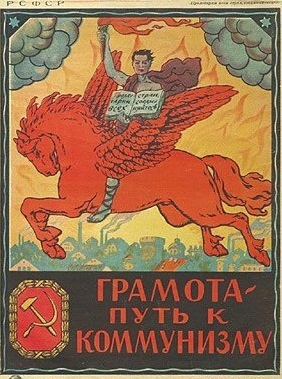

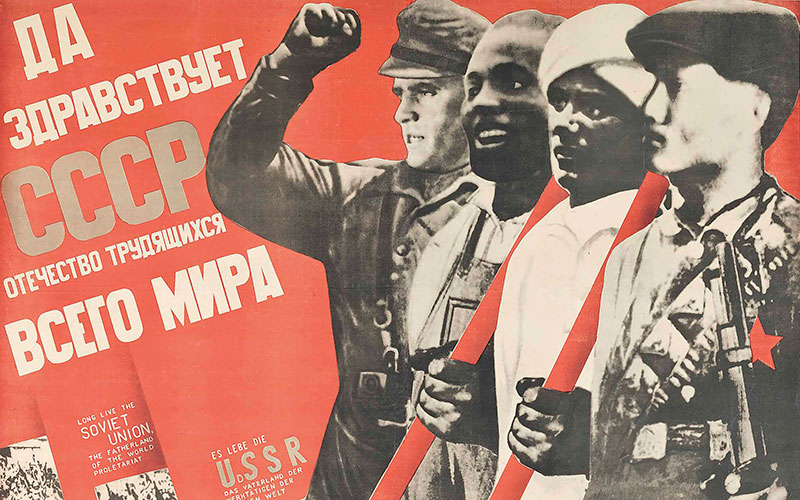

The global union of the working class which Alexandra Kollontine as well as Dada Amir Haider Khan are idealistically portraying is also one of the main themes of socialist realist art and literature as the official aesthetic of the soviet union. This art movement is characterized by putting a positive hero or heroine of the working class in the centre of story telling of the written word or the visual image. Often the hero is portrayed in a naturalistic idealized way as the well-muscled, youthful and healthy worker that is ready to fight the chains of capitalism and start a revolution to build a classless society in the name of communism and socialism. Even if the female heroine is not portrayed as often as the male, one can see an increasing representation and recognition of the role of women within the revolutionary narrative of the working class.

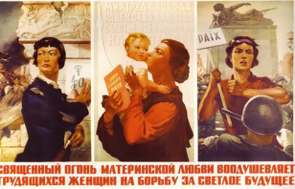

The postcard above is advertising celebrations to the International Women´s Day on the 8th of March which is acknowledging women of the working class from various backgrounds. Until today this day marks demonstrations and protests of the socialist women´s movement in 1917 as an event that represents women´s participation in the Russian Revolution. The new image of women is focusing on her identity as part of the proletariat although the narrative of women in their role as mothers of the revolution is still dominant as well. They were increasingly represented in different parts of society like educational and organizational institutions of the communist regimes and movements in place. One can argue that the society that is tried to be achieved is still a patriarchal one where women are not completely free from certain roles that they are described to because of their gender but that there is still change in how women are being given importance and are seen as part of the collective union of the working class. The aesthetics of the postcard are portraying the three women of diverse backgrounds as confident representatives of the international female proletariat. Them being positioned on the same level shows the attempt that racial or cultural divisions have no space in their unity. Their positive and happy appearance while looking into their socialist future is also an example how revolutionary individuals are characterized in socialist realist imagination. Being side by side representing their sisterhood working and fighting for the same goal is also an important image to be recognized. Although the stereotypical representation of “the asian” as well as “the african” women through accessories and the positioning of the white woman at the front does show that there is still a certain bias influencing that representation.

Communist and socialist ideology and their representation in different forms of socialist realist art are not completely free from race and gender divisions but one has to acknowledge that these hierarchies are being challenged and critized while at same time trying to focus on the collective identity that is uniting the working class as a whole.

The concept of communist internationalism allowed many people to dream of an alternative future that is restructuring society and has a new understanding of the value of every human being especially of the ones who have been through struggle in order to achieve this ideal state of liberation from the oppressive system of capitalist imperialism.