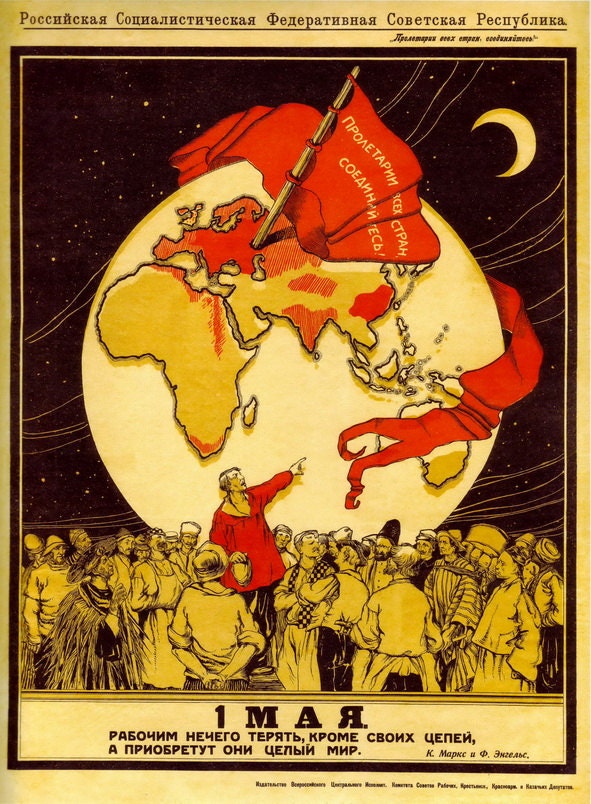

“I too, for the first time, felt in the red flag a symbol of victory over the exploiting system.”

The most striking aspect of this socialist poster is the individual around whom the art is focused. Two things stand out: his garb and the colour of his skin. These prominent features on display are what I will be using to link the poster to the extraordinary life of Dada Amir Haider Khan. This piece evokes a sense of pride that is attached to an individual’s heritage. Dada’s experiences in Moscow can be considered to be an emancipation of a similar ilk. Today we can see that his emancipation was temporary, but that’s precisely not the point. Whilst trying to understand his experiences, we must confine our understanding to the time he spent in Moscow, to get a sense of what that exposure meant to him, not to us. If we consider communist internationalism to be a failed endeavor which channeled elements of tokenism, we are doing a disservice to all those who temporarily regained their individuality in a world in which differences and divisions were rapidly being reified.

There’s an incident over the course of Dada’s university experience which I thought was particularly remarkable. Dada suggested to Comrade Intelginkoff that perhaps the use of one Russian language would be best suited to the interests of internationalism, a parallel being the use of English in the USA. Upon making this suggestion, Dada was criticized for being ultra-leftist. This interaction is what perfectly encapsulates his experience in Moscow. This is what sets you free. A man who had sailed the world twice had finally ended up in a space in which he was not expected to change or alter himself. The university promoted acceptance and tolerance by creating an environment in which you were not discriminated against. In this environment, Dada and his peers from around the world were not robbed of their individuality. Dada can be seen as the vanguard in the poster, representing the South Asian masses and experiencing a break from epistemic domination. This very epistemic domination is what compelled him to undermine the importance of his mother tongue and his identity, the value of was reinstated in this almost utopian spatial imagination that was realized within Moscow. What resulted was both a restoration of pride and a sense of belonging that had been lost since birth, throughout his voyage. His experience in the university was gradually healing the colonial rupture in time that had afflicted many. The body language of the individual in the foreground of the poster implies an existence that is unburdened despite the rupture.

What the poster allows us to imagine is an alternate reality which was very much a possibility, a way out, when Dada was enrolled in the university. This break from time resulted in socio-economic divisions and hierarchies being temporarily negated. While colonial discourse continuously reminded natives that there were intrinsic differences which separated Europe from the rest of the world, socialist reconstruction made an attempt at getting rid of that imposed linearity of time. In this context, language becomes essential component of an individual’s identity. In the background of the poster, we see mobilized masses who can also be perceived to be emancipated. While Dada’s own identity had been healed to a certain degree, this emancipation had eluded his people – the native inhabitants of South Asia. When Dada returned ‘home,’ he was deemed to be a threat to domestic peace and stability. His ‘home,’ instead of being a sanctuary, was plagued by the colonial epistemic framework which did not ascribe any value to native individuality.

Had the ways of communist internationalism prevailed, we perhaps would have viewed Dada as a hero of national liberation. But since it did not happen, his story and his struggles became obscured fragments in time. He dedicated his life to a cause he believed was larger than himself. It’s important to remember his sacrifice. It’s important to remember him.

“So for the first time in my life I began to understand things that had become unknown to me.”

.jpg)